When rabbis in Brooklyn spotted a tiny crustacean

swimming in New York City's tap water last spring, the

ensuing debate about whether it rendered the city's water

unkosher seemed like an amusing, but esoteric dispute in a

particularly exacting Jewish enclave.

But in the months since, the discovery has changed the

daily lives of tens of thousands of Orthodox Jews across the

city. Plumbers in Brooklyn, Manhattan and Queens have been

summoned to install water filters - some costing more than

$1,000 - and dozens of restaurants have posted signs in

their windows trumpeting that they filter their water. As a

result, an entirely new standard is being set for what

constitutes a kosher kitchen.

"I don't want people in the community to be uncomfortable

in my home," said Laurie Tobias Cohen, executive director of

the Lower East Side Conservancy, explaining why she put a

filter on the faucet of her Washington Heights apartment.

The issue has created the perfect conditions for a

Talmudic tempest, allowing rabbis here and in Israel to

render sometimes conflicting and paradoxical rulings on

whether New York City water is drinkable if it is not

filtered. As with the original Talmudic debates, the

distinctions rendered for various situations have been

super-fine, with clashing judgments on whether unfiltered

water can be used to cook, wash dishes, or brush teeth, and

whether filtering water on the Sabbath violates an obscure

prohibition.

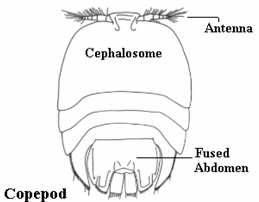

The creature, a crustacean known as a copepod that comes

in several species, is found in water all over the world and

is perfectly harmless. But it is a distant cousin of the

dreaded shrimp and lobster, shellfish whose consumption

violates the biblical prohibition against eating water-borne

creatures that lack fins and scales.

The prohibition refers only to species that can be seen

with the unaided eye - not, say, an amoeba - and the

question of whether the copepod is indeed visible is central

to the dispute. Some are so small as to be invisible, while

others can grow to a millimeter and a half in length, large

enough to be seen in water as small white specks.

The tumult is confined largely to New York because it is

one of the few cities that is exempt from federal filtering

requirements. Boston and Seattle are also exempt, but they

have nothing like the city's numbers of Orthodox. In New

York City, there are 331,200 Orthodox Jews, a third of the

Jewish population, according to a 2002 study done for UJA-Federation

of New York.

The sure winners in this theological tizzy are plumbers

and water filter entrepreneurs.

"We've had a 500 percent increase in sales," said Houston

Tomasz, vice president of Sun Water Systems of Fort Worth,

Tex., which manufacturers the Aquasana filter, whose

full-house version can cost more than $1,500 installed. "Not

everyone was a kosher Jew. When you start talking about

visible bugs in water, Jews aren't the only people who

care."

In Brooklyn, a landlord started a firm overnight that he

called Eshel Filters. In September just before the Sukkot

holidays, when many Jews invite neighbors over, the company

installed 30 filters a day ranging in cost from $99 to

$1,150. Its motto: "The bug stops here."

The controversy is indicative of deepening religious

conservatism in the American Orthodox world. William B.

Helmreich, a professor of sociology and Judaic studies at

the City University of New York Graduate Center, said that

"in a society where people feel via the Internet and

television their very values are under constant attack,

there's a need for people to reassert their level of

religiosity, and one way this is done is by discovering new

restrictions which give people the opportunity to

demonstrate their adherence to their faith."

For generations, the most pious Jews - even revered

rabbis like Joseph B. Soloveitchik and Moses Feinstein -

drank unfiltered New York water with no evident concern. But

six months ago, a group of Brooklyn rabbis were examining

some lettuce imported from Israel that was supposed to be

bug-free, but which appeared to have insects on its leaves.

After an investigation, they determined that the "bugs" had

arrived after the lettuce was washed in New York City water,

and said that in the right light they could see the telltale

specks with their own eyes.

At some point, a delegation of rabbis took a field trip

to the city's reservoirs and asked officials some detailed

questions about the origins of the water and the copepods.

(Of the three reservoir systems, only one - the Croton - is

in the process of introducing filtering, with a plant that

will cost an estimated $1 billion but will not be completed

before 2010.)

The question lingered unresolved by a major communal

authority until the Orthodox Union, which certifies as

kosher 275,000 products in 68 countries, weighed in last

August after checking some water samples.

"When they saw the first sample they didn't feel it

reached the threshold of being visible," said Rabbi Menachem

Genack, the rabbinic administrator for the Orthodox Union.

"What changed people's minds is when they saw a sample taken

from a pond and saw them scooting around. Those are beyond

the threshold."

The Orthodox Union recommended that restaurants and

caterers under its supervision filter their water before

using it in drinking and cooking, a policy that quickly was

adopted by many homes as well. The policy considered

different practical possibilities. Dishes may be washed by

hand in unfiltered water, it said, if the dishes are towel

dried or left to drip-dry without puddles of water in them.

But it also said water should not be filtered on the

Sabbath because one of the 39 varieties of work forbidden by

the sages includes "selection," or sifting of food, like

separating wheat from the chaff or raisins from a noodle

pudding.

The organization issued the policy to make sure even the

most stringent consumers would be satisfied that what they

were eating was kosher to the highest standards. But a

debate continues within its own rabbinical ranks about how

the filtering policy should be applied in ordinary homes,

and some rabbis have suggested the filtering frenzy may have

gone too far.

Rabbi Yisroel Belsky, one of the leaders of Torah Vodaath

rabbinical seminary in Brooklyn and an important voice on

Orthodox Union kosher matters, said in an interview that

there was no requirement to check for things that were

impossible to see in the years before microscopes.

"If everybody goes around thinking that whoever doesn't

filter water is actually eating things that are treyf," he

said, using a Hebrew word for unkosher, "there will probably

be all kinds of disputes between individuals and marriage

problems that can cause a cleavage."

Many Jews have been left confused. Fran B., a marketing

manager for a software firm who asked that her last name be

withheld, said she did not want to tear up the granite

countertops in her Manhattan apartment to install a filter

under the sink, so she lugged bottled water from the

supermarket.

"On the one hand, I'm drinking bottled water, but on the

other hand I'm eating at friends' houses who have never even

heard of this," she said.

Others are perplexed about whether to filter at all,

filter on Sabbath, or filter for purposes of cooking,

washing dishes or brushing teeth.

"The difference in opinions is driving a lot of people

crazy," said Rabbi Ephraim Buchwald, director of the

National Jewish Outreach Program in Manhattan, who hauls

bottled water to his apartment so he will not have to filter

on Sabbath. "You can't imagine what a turmoil it is."

In an article in The Jewish Press, David Berger, a

professor of history at the City University Graduate Center

and a rabbi, said, "The notion that God would have forbidden

something that no one could know about for thousands of

years, thus causing wholesale, unavoidable violation of the

Torah, offends our deepest instincts about the character of

both the Law and its Author."

Rabbi Moshe Dovid Tendler, who is a professor of biology

and of Talmudic law at Yeshiva University, said he spotted

the telltale specks only after first looking at copepods

through a 60-power dissecting microscope.

But having seen them, he said he thought they should be

filtered out. Nevertheless, he does not believe the filters

should be turned off on Sabbath - Jewish law already allows

people to pick algae or other vegetation out of water. And

he certainly does not worry about whether pious Jews who

drank unfiltered tap water in the past sinned.

"The hidden things belong to God," he said. "We are

responsible for what we see. If you don't know about it and

don't see it, then it doesn't exist. So those who drank the

water before were drinking kosher water."